ਦਿਲ ਦਾ ਨੀ ਮਾੜਾ Legends Never Die: REMEMBERING SIDHU MOOSE WALA

The world is mourning Sidhu Moose Wala’s death. From Drake in Canada to Burna Boy in Nigeria, many rappers and international artists have come together with the rest of the globe to mourn the gunned down rapper who had his own unique take on eliminating apathy within Panjabi youth.

Image from Sidhu Moose Wala’s Moosetape

Sidhu Moose Wala, also known as Shubhdeep Singh Sidhu, arrived in Brampton, Canada as an international student from an almost remote village in Mansa, Panjab called Moosa. In 2016, he wrote the lyrics for a song for another artist. He quickly rose in fame due to the recognition he was receiving as a lyricist, and in 2017, released his first single, “G Wagon.” After that, he produced hit after hit, with various albums and mixtapes released under 5911 Records and his own label.

Turning Stigma on its Head

Sidhu embodied the dream of coming up. Like many newly arrived in Canada, Sidhu was an international student, and marginalized community member, coming from a land riddled with intergenerational trauma, lack of opportunities for growth and political tension.

Sidhu’s coming up story is integral to the morale of many. In Canada, rampant mistreatment of international students still exists today, where, they not only face racism and discrimination, but are often exploited as migrant labourers and, as Baaz News reports, “cash cows for post-secondary institutions and governments.” International students also fill integral labour jobs, and also are subjected to discrimination and exploitation with housing within the Panjabi communities scattered throughout the country.

Baapu, Yes I Am Student – Sidhu Moose Wala, Tarnvir Jagpal, Intense – Tips Punjabi via YouTube

ਮੁਸੀਬਤ ਤਾਂ ਮਰਦਾ ਤੇ ਪੈਂਦੀ ਰਿਹੰਦੀ ਏ

ਦਬੀ ਨਾ ਤੂ ਦੁਨਿਯਾ ਸਵਾਦ ਲੈਂਦੀ ਏ

“If you progress, you’ll be met with hate,

Trouble dies and falls, SO don’t let the world GET A taste OF you”

Expressing the struggle with his own twist

In the 1980s and 1990s, history documented a counter-movement of the Black American community through gangster rap, which was utilised as a medium to express communal frustration over a lack of personal and community agency, racism, exploitation and labelling, poverty, as well as an overall lack of institutional resources supporting the success, life and liberty of Black Americans.

Sidhu Moose Wala, although known as a rapper internationally, was also an extremely talented Panjabi folk singer. He authentically brought our roots to the genre. Panjabi’s and Sikhs have been heavily influenced by gangster rap even though we are outside of the Black community due to our community’s marginalisation as a minority community in and outside of India. A lot of our collective trauma as a community also stems from racism throughout our immigration journeys post colonisation, the 1947 Partition and mistreatment onwards. We are also a heavily displaced people with often, roots forcefully ripped from our own homelands time and time again. The struggles arguably have their immense differences and unique hardships, but the fundamentals of uprising against struggle and being authentic to one’s self expression remain the same.

Sidhu’s messaging relays something integral: that we are more concerned as a society about banning those with a message of truth and autonomy than creating avenues for misled youth engaging in violence to step into their own power and build meaningfully for themselves and their communities. Still, today, we shoot the messenger – we don’t tackle the conditions, traumas, and cultures that bring people towards such violence and chaos.

Today, Panjabi is in scarcity even in Panjab. Sidhu was not only a talented rapper and singer, but he was a maestro of the Panjabi language, communicating it and teaching more of it to diaspora kids through rap and folk songs. He was a powerful force encouraging us to sing and rap in our mother tongues and learn what the words mean. Through our mother tongue, he motivated youth to step into their power and be authentic to themselves.

Yet, despite the fact that he is arguably the greatest youth icon of this generation, his method of being and relaying his messages were constantly deemed notorious. His subject matter and bluntness in expressing his thoughts and feelings brought out something deeply suppressed in all of us who listened to his music. He and his image bore the brunt of it when youth got violent at his international shows. The 0.1% that overglorified the violence in his branding and messaging quickly brought upon public safety concerns for his shows – further creating notoriety in his messaging. In my own experience in the industry, I have personally seen how various institutions have manipulated his image instead of working with music festivals and concert producers to create concrete safety plans, messaging condemning violence at prospective shows, and overall, tackling Vancouver’s gang problem ways that are effective and preventative.

Yet, Sidhu’s messaging relays something integral: that we are more concerned as a society about banning those with a message of truth and autonomy than creating avenues for misled youth engaging in violence to step into their own power and build meaningfully for themselves and their communities. Still, today, we shoot the messenger – we don’t tackle the conditions, traumas, and cultures that bring people towards such violence and chaos.

295 – Sidhu Moose Wala & The Kidd from Moosetape tells youth to keep their heads up and not fall into anything that compromises their integrity.

ਐਥੇ ਬਦ੍ਨਾਮੀ high rate ਮਿਲੂਗੀ

ਨਿਤ Controversy Create ਮਿਲੂਗੀ

ਧਰ੍ਮਾ ਦੇ ਨਾਮ ਤੇ Debate ਮਿਲੂਗੀ

ਸਚ ਬੋਲੇਗਾ ਤਾਂ ਮਿਲੂ 295

“There will be a high rate of notoriety

Daily Controversy Create

Debate in the name of religion

Speak the truth then meet 295”

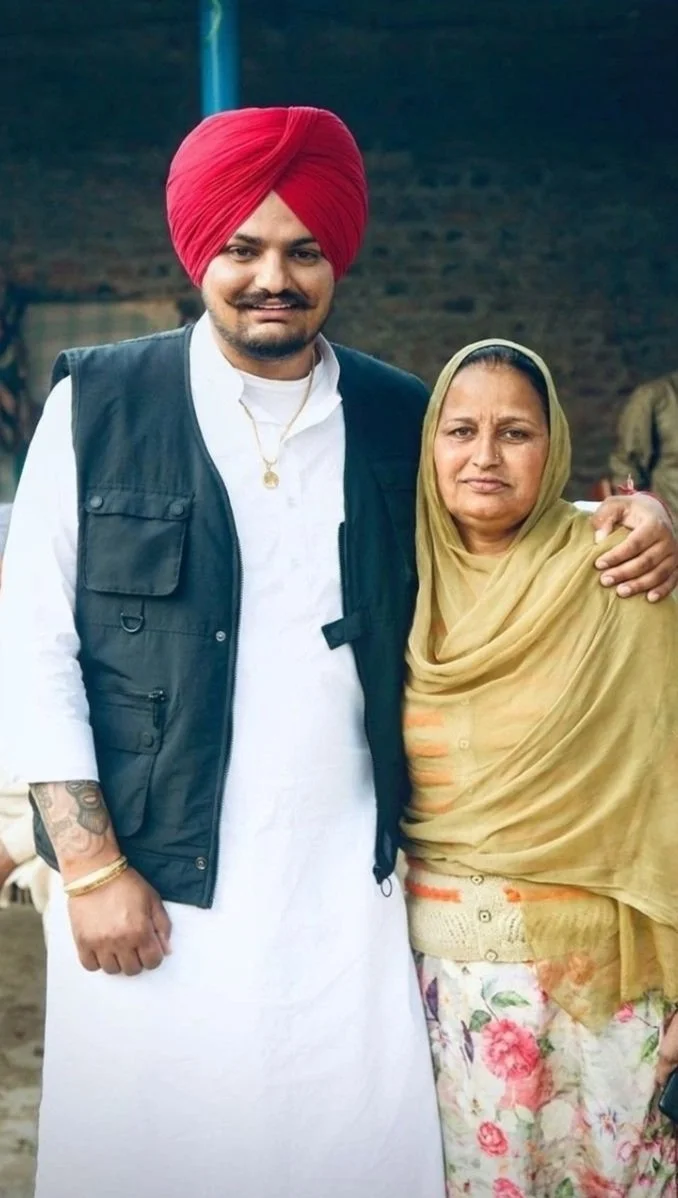

Shubhpreet Singh with his Mom in Panjab.

The Media We Consume Is Doing Exactly What Sidhu, And So Many Before Him Called Out

The first thing most of the world woke up to with the news of Sidhu’s death includes grotesque imagery in circulating videos and photos. We clearly see people taking videos of Sidhu’s (almost) lifeless body rather than helping him out of the jeep. A mother and father lost their only child, and the media’s job is to honour him and them – parents who lost their only child.

Media maligns those who speak the truth, advocate for their communities, unabashedly speak their own language. We’ve seen this happen plenty of times with American gangster rappers. The push to notoriety is misleading, as, in many interviews with those who watched Sidhu grow up, come to Canada, and move back to his pindh (village) have seen the contributions he made to its progress. This includes encouraging girls to go to school and often, waiting for them to return from school at the bus stop to avoid rampant eveteasing, female inferiority and rape culture that is so prevalent in India. And that’s one thing that’s consistent throughout Sidhu’s music – he never disrespected women in his lyrics to be a bad ass. Frequently, he honoured his mother and created lyrics similar to late Panjabi legend Surjit Bindrakhia, who spoke of women in relation to men with jest and joy, bringing the toughness ultimately back to himself, not through the abuse of women.

Rumours of whodunit also interweave political complexity in a region riddled with corruption and the continued suppression of youth well after protests. Ultimately, the media circus cannot take away from the heavy, personal loss fans feel. The rest is truly noise.

Image via MistaClix on SoundCloud

Heavily Influenced by Makiaveli

Sidhu was a big follower of Tupac Shakur, ofen citing his imagery through fashion the Makiaveli mindset in a lot of his lyrics. As a marginalised, minority community, our own icon’s parallels to Tupac’s life and death are uncanny: his fight for self-sovereign thought, liberation of self, and standing up for the rights of his community rose with him during his fame, something that also continued to exist with Tupac during his rise to fame. We take solace in knowing that he is resting with his icon – the imprint of his work on the world is mighty, and it’s enough.

Sidhu’s impact on the Panjabi music industry, in educating youth about our ongoing struggles as a community, advocating for international students, standing up for the truth, and stating things as they are no matter who intimidates us into silence can be seen in the celebration of his life. Panjabis are coming together; whether it's in the diaspora, or in Panjab across borders that divide us, too.

It’s hard not to be dazed and jaded, but we know that legends never die. Sidhu Moose Wala’s work will be immortalised – and the movement of speaking our truth that his existence sparked will continue to emerge from his embers.

The Last Ride – Sidhu Moose Wala & Wazir Patar immortalises the artist.